Ι. A dream and a reality

I always thought that it was because of my lack of orientation that I often got lost in that structure: It was a rectangular building with a central atrium and large windows that overlooked the interior patio. A cold night, walking past the building I suddenly realized why I felt out of place in its exterior courtyard. Although I was fully aware of my place of work inside the building, looking at it from the outside, I could not locate the window of my office. I knew it was on the third floor. But which one was it? I tried to remember -but all my memories concerned views from the interior atrium, people working, chattering, going up and down- but not the exterior ones. In an instant I recalled that the window was placed over my head and even though the morning light came in, I never actually had visual relationship with the surrounding buildings. My work office was a contemporary kind of a jail. Its cozy interior atmosphere and the happy faces of my coworkers never made me question what was lying outside its protectively closed walls.

///

Ho sempre pensato che fosse a causa del mio scarso senso d’orientamento che mi perdevo spesso in quella struttura: un edificio rettangolare con un atrio centrale e grandi finestre che si affacciano sul patio interno. Una notte fredda, passando davanti all’edificio, mi resi improvvisamente conto del perché mi sentissi fuori posto nel suo cortile esterno. Sebbene fossi pienamente consapevole di dove fosse la mia postazione di lavoro all’interno, guardandolo dall’esterno, non sono riuscita ad individuare la finestra del mio ufficio. Sapevo che era al terzo piano. Ma quale era? Ho cercato di ricordare, ma tutti i miei ricordi riguardavano viste dall’atrio interno, persone che lavoravano, chiacchieravano, salivano e scendevano, ma non quelle esterne. In un istante ho ricordato che la finestra era posizionata sopra la mia testa e, nonostante entrasse la luce al mattino, non ho mai avuto relazioni visive con gli edifici circostanti. Il mio ufficio era una sorta di prigione in stile contemporaneo. La sua accogliente atmosfera interna e le facce felici dei miei colleghi non mi hanno mai fatto dubitare di ciò che stava al di fuori delle sue mura protette.

And then I woke up. Rethinking about it, the meaning of the dream was double. It was not the sense of disorientation that scared me the most but rather a sense of alienation and enclosure which was provoked by the lack of ‘real’ communication. (And although it was ‘just a dream’ all the architectural elements were there: the windows, the walls, the atrium, the people). Good design goes far beyond fulfilling everyday needs and having beneficial effects in a user’s psychology. It is rather about allowing users to be aware of who they are in the world, conscious of the places and the people that surround them and eventually of what they deserve in life. Thinking deeper about it, I am getting more and more convinced that design has truly the power ‘to dignify and make people feel valued, respected, honored and seen (1)’.

///

E poi mi sono svegliata. Ripensandoci, il sogno aveva un duplice significato. Non è stato il senso di disorientamento che mi ha spaventato di più, ma piuttosto un senso di alienazione e di chiusura che è stato provocato dalla mancanza di una comunicazione “reale”. (E sebbene fosse “solo un sogno” tutti gli elementi architettonici in cui c’erano: le finestre, i muri, l’atrio, le persone). Un buon design va ben oltre il soddisfare le esigenze quotidiane ed avere effetti benefici nella psicologia dell’utente. Si tratta piuttosto di consentire agli utenti di essere consapevoli di chi sono nel mondo, consapevoli dei luoghi e delle persone che li circondano e, infine, di ciò che meritano nella vita. Pensando più a fondo, mi sto sempre più convincendo che progettare ha davvero il potere di “nobilitare e far sentire le persone apprezzate, rispettate, onorate e viste”. (1)

ΙΙ. A restroom, a courtyard & a city

The previous statements have a lot to do with social exclusion and how design unconsciously blocks or restricts users, because it repeats the errors of the past, perpetuating ideas which shouldn’t represent our contemporary societies. In other words, design still reflects old fashioned notions. From the usual yet unequal queues in women’s restrooms (2) to the way our cities are shaped (3) we can witness of lots of silent inequalities that take place in our societies because design allows it: wheelchair users whose access is still difficult in public places, elderly people who don’t have enough time to cross a street in a junction, unequally segregated playgrounds for children, parks that are considered unsafe, minorities that suffer from rise in homelessness. These examples are by no means an exhaustive list of how injustice foments design, but renderings of how complex and deep the problem is.

///

Le dichiarazioni precedenti hanno molto a che fare con l’esclusione sociale e in che modo il design blocca o limita inconsciamente gli utenti, perché ripete errori del passato, perpetuando idee che non dovrebbero rappresentare le nostre società contemporanee. In altre parole, il design riflette ancora nozioni vecchio stile. Dalle solite ma ineguali code nei bagni delle donne (2) al modo in cui le nostre città sono modellate (3) possiamo assistere a molte disuguaglianze silenziose che si verificano nelle nostre società perché il design lo consente: utenti su sedia a rotelle il cui accesso è ancora difficile nei luoghi pubblici, persone anziane che non hanno abbastanza tempo per attraversare una strada in un incrocio, campi da gioco per bambini segregati in modo diseguale, parchi considerati non sicuri, minoranze che soffrono di aumento dei senzatetto. Questi esempi non sono affatto un elenco esaustivo di come si seminano i fomenti dell’ingiustizia, ma i rendering di quanto sia complesso e profondo il problema.

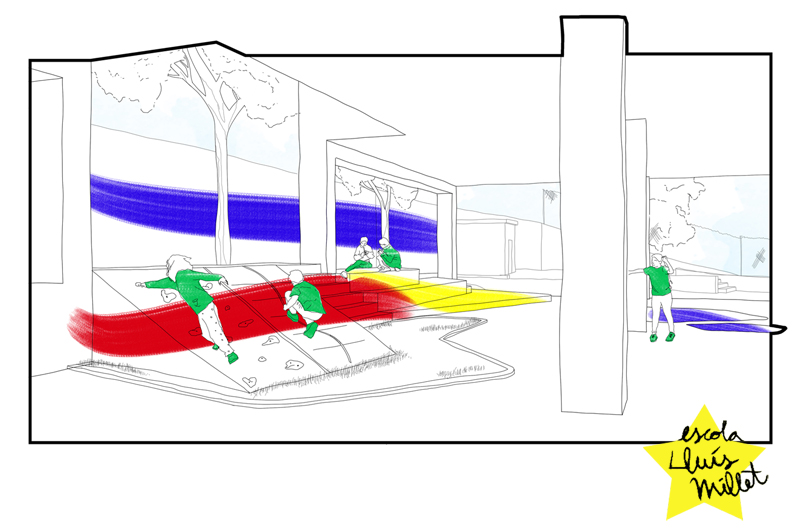

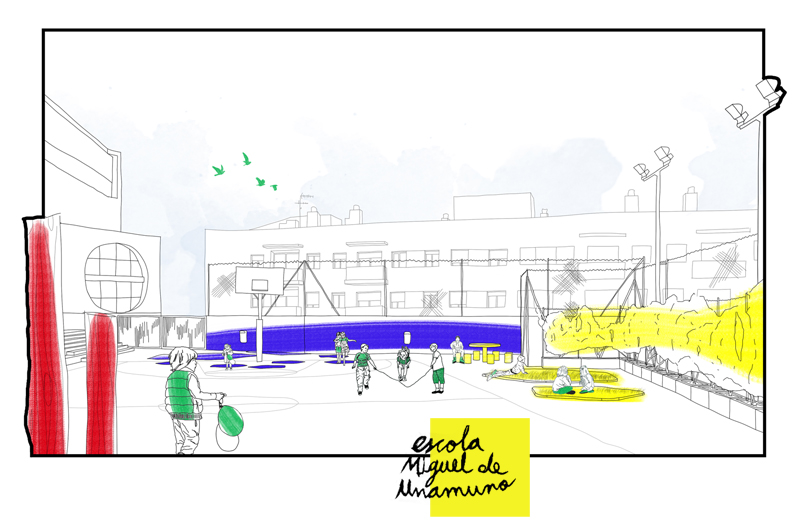

Are our schools’ courtyards cruel? Do they promote equality and coexistence? Photos and sketches from the initiative ‘Rethinking the use of school playgrounds’ launched by Equal Saree in Barcelona.

Yet there are some optimistic initiatives.

///

Eppure ci sono alcune iniziative ottimistiche.

– Superblock (4) is an initiative launched in Barcelona. Its aim is to transform streets which were previously dominated by cars into pedestrian roads and mix-used public spaces, meanwhile facilitating public transport – this affects everyone in a city but impacts disproportionately low income users and vulnerable minorities (5).

– The city of Vienna (6) tries to eliminate gender discrimination by planning and designing playgrounds that ensure equal participation of boys and girls. Similarly, Equal Saree (7) in Barcelona promotes ‘fair play’ by designing spaces where different kinds of activities are generated at the same time, giving everyone access to the school’s courtyard.

– The municipality of Leipzig (8) tries to keep the city affordable for its own residents by promoting models of collective, cooperative and solidarity-based housing through the construction, renovation and modernization of rental housing for low-income persons and the construction of day nurseries. The aim of the initiative is to facilitate these people as well as young children, elderly and disabled persons, students and single-parent families, migrants and refugees and meanwhile eliminate gentrification.

///

– Superblock (4) è un’iniziativa lanciata a Barcellona. Il suo scopo è quello di trasformare le strade precedentemente dominate dalle macchine in strade pedonali e in spazi pubblici a uso misto, facilitando nel contempo i trasporti pubblici – il che colpisce tutti quanti in una città ma ha un impatto sproporzionato su utenti a basso reddito e minoranze vulnerabili (5).

– La città di Vienna (6) cerca di eliminare la discriminazione di genere pianificando e progettando campi da gioco che garantiscano un’eguale partecipazione di ragazzi e ragazze. Allo stesso modo, Equal Saree (7) a Barcellona promuove il “fair play” progettando spazi in cui vengono generati diversi tipi di attività, dando a tutti l’accesso al cortile della scuola.

-Il comune di Lipsia (8) cerca di mantenere la città alla portata dei propri residenti promuovendo modelli di alloggi collettivi, cooperativi e garantiti dalla solidarietà attraverso la costruzione, il rinnovamento e l’ammodernamento di alloggi in affitto per persone a basso reddito e la costruzione di asili nido. Lo scopo dell’iniziativa è facilitare queste persone così come i bambini piccoli, le persone anziane e disabili, gli studenti e le famiglie monoparentali, i migranti e i rifugiati e nel frattempo eliminare la gentrificazione.

Cities are complex organisms shaped by numerous forces. Yet the aforementioned cases are optimistic examples of what design can do if implemented thoughtfully in urban design, supported by the local communities and the state. As John Cary (1) mentions in his Ted talk ‘Once you see what design can do, you can’t unsee it. And once you experience dignity you can’t accept anything else (…). Dedicating more practices to the public good, will not only create more design which is dignifying but it will also dignify the practice of design’.

As architects, engineers and designers, it is in our hands to build up resilient cities, minimizing inequalities in urban and domestic space, promoting fair shared communities that support, include and do not restrict.

///

Le città sono organismi complessi formati da numerose forze. Tuttavia, i casi di cui sopra sono esempi ottimistici di ciò che il design può fare se implementato in modo ponderato nella progettazione urbanistica, supportato dalle comunità locali e dallo Stato. Come menziona John Cary (1) nel suo TEDtalk “Una volta che vedi cosa il design può fare , non puoi non vederlo. E una volta che si sperimenta la dignità, non si può accettare nient’altro (…) Dedicare più pratiche al bene pubblico, non solo creerà più design più dignitoso, ma nobiliterà anche la pratica del design “.

Come architetti, ingegneri e designer, è nelle nostre mani costruire città resilienti, minimizzare le disuguaglianze nello spazio urbano e domestico, promuovere comunità condivise eque che sostengano, includano e non limitino.

1: John Cary’s speed on TedX

2: Researchers conclude that women need twice as many public washrooms as men due to ‘time-consuming factors related to their clothing, menstruation and anatomical differences’. Yet generally the ratio of the lavatories is 1:1. In New York, a legislation passed in 2005 required all new bars, arenas and theaters to have a 2:1 ratio of women’s to men’s stalls. From 1987 to 2006, at least 21 states supported this legislation. More ontheatalantic.com and on Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing, by Harvey Molotch & Laura Noren, New York University Press, 2010

///

Le ricerche concludono che le donne hanno bisogno di un numero doppio di bagni pubblici rispetto agli uomini a causa di “fattori che richiedono tempo in termini di abbigliamento, mestruazioni e differenze anatomiche”. Tuttavia, in genere il rapporto tra i servizi igienici è 1: 1. A New York, una legislazione approvata nel 2005 imponeva a tutti i nuovi bar, arene e teatri di avere un rapporto 2: 1 tra le donne e le bancarelle degli uomini. Dal 1987 al 2006, almeno 21 stati hanno appoggiato questa legislazione. Più su theatlantic.com e su Public Restrooms and the Politics of Sharing, by Harvey Molotch & Laura Noren, New York University Press, 2010

3: Interesting comments about the structure of American cities and the distribution of facilities in them especially in the cases of vulnerable social groups in ‘What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work’ by Dolores Hayden (e.g. concerning divorced women with children p.175 ‘The typical divorced woman seeks housing, employment and child care simultaneously. She finds that matching her complex family requirements with various available offerings by landlords, employers and social services is practically impossible.’)

///

Commenti interessanti sulla struttura delle città americane e sulla distribuzione delle strutture in esse, specialmente nei casi di gruppi sociali vulnerabili in “Come sarebbe una città non sessista? Speculazioni sull’edilizia abitativa, la progettazione urbana e il lavoro umano “di Dolores Hayden (ad esempio riguardo alle donne divorziate con figli pag. 175” La tipica donna divorziata cerca contemporaneamente alloggio, lavoro e assistenza all’infanzia. Si riscontra che è praticamente impossible trovare il giusto equilibrio tra le varie opzioni disponibili offerte da proprietari, datori di lavoro e servizi sociali.”)

4: More on ‘Cars dominate cities today. Barcelona has set out to change that’. Vox.com

5: More on ‘America’s Unfair Rules of the Road-How our transportation system discriminates against the most vulnerable’. slate.com

6: More on ‘Parks -ways to implement gender mainstreaming’ wien.gv.at

7: More on ‘El patio de la escuela Joan Solans– Diagnosis y propuestas de mejora con perspectiva de género.’ equalsaree.org

8: More on ‘How Leipzig is reinventing housing’ goethe.de